Vol. 5: Hoax

Friedrich Wilhelm Rust’s life is a little bit of a magical vortex for discoveries; somehow I keep finding little Rustian tendrils sprouting out and weaving imperceptibly into the stories of bigger historical figures, or surprising new manuscripts that change my mind about what Rust was trying to do.

But for today, the juiciest story: the Rust Hoax.

—-

F.W. Rust died in 1796. With his wife Henriette Niedhardt, he fathered 8 children, 6 of whom lived to adulthood. I might return to a couple of those children another time (spoiler: one was friends with Beethoven), but I’m going to fast-forward to F.W. Rust’s grandson, the confusingly-named Wilhelm Rust (1822–1892).

Wilhelm Rust (1822–1892): Important, if mildly sketchy.

Wilhelm Rust was an important figure in the early history of musicology; he collected Bach manuscripts and made mammoth contributions to the Bach-Gesellschaft, the first attempt to publish all of Bach’s works in “clean” editions without editorial changes. He also literally followed in Bach’s footsteps by becoming organist and Thomaskantor in Leipzig, a position Bach held from 1723–1750.

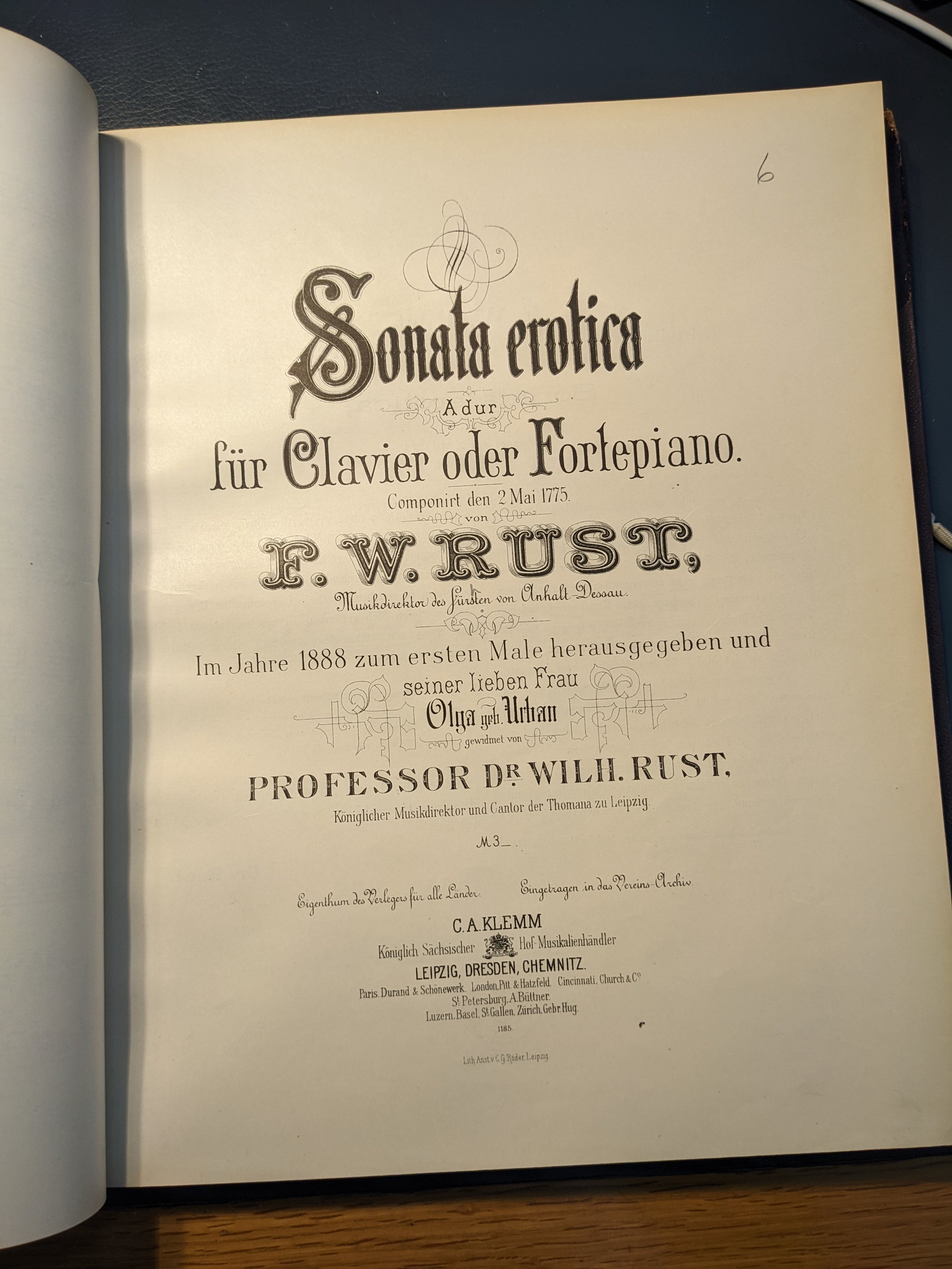

In the 1880s, Wilhelm published a few of F.W. Rust’s piano sonatas. In flowery written prefaces, he framed the pieces in the loftiest terms, suggesting that they showed Rust as a visionary genius who preempted the stylistic innovations of later composers like Beethoven and Mendelssohn. Given this glowing review and their evocative titles (like “Sonata erotica”), prominent musicians quickly endorsed these works, and they began to be widely performed.

But it was all a ruse.

After Wilhelm Rust died in 1892, his manuscripts ultimately landed in the Berlin Royal Library, now the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. There, in 1912, Dr. Ernst Neufeldt discovered F.W. Rust’s original versions of the piano sonatas, and found that Wilhelm Rust’s published versions had vastly misrepresented F.W. Rust’s work; Wilhelm had changed large tracts, added evocative titles, and inserted the “advanced” harmonies and motifs that had attracted widespread admiration. Wilhelm even added entirely new movements - then alluded in his prefaces to life events that had led F.W. Rust to compose those same movements.

After this ruse came to light, F.W. Rust’s popularity tanked for the remainder of the 20th century and his works were rarely played. The wrongdoing was entirely on Wilhelm’s part rather than F.W.’s, but somehow it seems like the whole subject became slightly taboo. Wilhelm Rust, already deceased by the time the fraud was revealed, remains remembered mostly for his contributions to Bach scholarship.

Today, when I visited the Staatsbibliothek to view some Rust manuscripts, the librarian on staff good-naturedly reminded me to not mark them up, “even if you feel like Rust needs correcting!”

Music Reading Room, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin

—-

My time as a visiting scholar at the University of Cambridge is supported in part by funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, with additional research funding from the Mitacs Globalink Research Award. The present European component of my research is supported by the American Bach Society's William H. Scheide Research Grant.